- Home

- Peter Fiennes

Footnotes Page 12

Footnotes Read online

Page 12

Slavery had been ‘unsupported on English soil’ since 1772 and finally abolished across the British Empire in 1833, but Douglass was the force who reignited the anti-slavery movement and spread it across the globe, borne aloft by surging waves of British outrage and self-satisfaction. After he spoke in Edinburgh, over 10,000 women sent a petition to Washington demanding an end to slavery. And in Bristol, the day after he arrived in the city, he thrilled a crowd in the Victoria Rooms with the soaring passion of his speech (but not before the mayor had surprised the local paper by pouring Douglass a glass of water).

‘You may’, Douglass began, have ‘heard of America, 3,000 miles off, as the land of the free’, but the truth is that the real sound coming from the South ‘is the clank of the fetters and the rattling of the chains, which bound their miserable slaves together, to be driven by the lash of their driver on board the ships for New Orleans, there to be sold in the market like brutes’.

A few days later Douglass was in Exeter, making ‘A Call for the British Nation to Testify Against Slavery’. He realized that he needed Britain’s help in the fight against American slavery, or at least the support of its people, even though anti-British sentiment in America might make this support counter-productive. But as he said that night in Exeter:

[Slavery] is such a monstrous system, such a giant crime, that it begets a character favourable to its own existence, vanquishing the moral perception, and blinding the moral vision of all who come in contact with it; and a nation has not the moral energy necessary to its removal.

Douglass knew exactly how to tickle his patriotic, West Country audience, and to a final crescendo of wild cheering he shouted:

I will go to the land of my birth, I will proclaim it in the ears of the American people, whether I’m in a state of slavery or freedom, while I have a voice to speak it shall be raised in exposing the guilt of the slave-owners, and in contrasting the munificent freedom of monarchical England, with the slave-holding, man-stealing, woman-whipping, degradation of democratic republican America.

Anyway, I’m going to slide past Bristol and Bath, lovely as they are. Time is short and they’re quite busy enough reassessing their own histories without any help from me.

We can also miss Gloucester. It’s ‘a low, moist place’ says Celia, and she had ‘the worst Entertainment’ and ‘strangers are allwayes imposed on’, and there were very few books in the library and that should be warning enough. Celia stayed outside Hereford with her cousin, Pharamus Fiennes (I mention this so I can write his long-vanished name), and when she rode into the city thought it was ‘a pretty little town of timber buildings, the streets are well pitched and handsome’ and there were plenty of fish in the ‘thick and yellow’ river. Celia never did venture into Wales. She had heard that ‘the inhabitants go barefoot and bare leg’d’ and were ‘a nasty sort of people’. But waiting here in Hereford, in the year 1188, about to embark on a long tour of the country, is Gerald of Wales – and he can explain quite how wrong she was.

Five

‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’

‘Wealth and violence seem to sustain us in this life, but after death they avail us nothing.’

Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales,

South and Central Wales, March and April 1188

I cross the border that separates England from Wales on a minor road near Presteigne, just north of the A44. It is an early morning in June and a dense mist is rolling down the green hills and seeping through the hedgerows. With visibility squeezed to a few awkward yards, I am driving slowly with the windows down, the car’s engine clattering off the high banks of the narrow lanes and the wipers flapping and squawking at the murk. On either side, the verges are radiating wet new life: hawthorn blossom, red campion, cow parsley, flowering nettles, a twist of woodbine and the last of the native, ‘English’ bluebells. ‘Araf’, says the first sign in Welsh: easy does it.

I stop at New Radnor and the mist seems to lift a little, or turn wetter. A mizzle, let’s say. The English language is awash – drenched – with ways of describing the stuff that falls from the sky. I’m afraid I can’t tell you about Welsh, but it surely won’t be any different. In Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Buried Giant, set in a post-Arthurian time of invading Saxons and traumatized Britons, much of the land is veiled and muffled by an impenetrable fog. Something unspeakable is being hidden – the truth, perhaps, about what really happened when two peoples met. An ageing Sir Gawain even appears out of the gloom. It is an unsettling book, and it asks impossible questions, in a halting language, about what we choose to remember – and what it may be better we learn to forget – about the worst of crimes. But when did you ever hear of a border being agreed with a smile and a friendly handshake? Someone has always lost something.

I am following in the footsteps of a man called Gerald de Barry, otherwise known as Giraldus Cambrensis – or, in plain English (a language he despised), Gerald of Wales. And this is how he starts his book The Journey Through Wales:

In the year AD 1188, Baldwin, Archbishop of Canterbury, crossed the borders of Herefordshire and entered Wales.

The border would have been in a different place in 1188, deeper into what is now England and closer to Hereford, I imagine, and the transition from one country to the other was more significant than it is today, albeit less abrupt (there’s no avoiding the signs bidding us all ‘Croeso i Gymru’). Archbishop Baldwin was leading an urgent mission into Wales to sign up recruits for a third crusade to the Holy Land. The previous year Jerusalem had fallen to Salah ad-Din (or ‘Saladin, the leader of the Egyptians and of the men of Damascus’, says Gerald), and Baldwin had been ordered by Henry II, ‘the king of the English’, to persuade the ferocious Welsh fighting men, especially their famous archers, to ‘take the Cross’ and travel to the Middle East to help reverse this cataclysmic outrage. Gerald, the Archdeacon of Brecon, whose Norman grandfather had married a Welsh princess, had been brought along for his diplomatic skills and his blood ties to almost every important Welsh family in south Wales. It was not known, until the mission arrived, quite how welcoming some of the Welsh would be.

There was another, and not just incidental, reason for Baldwin’s trip: it would give him a chance to preach in all four Welsh cathedrals and thereby affirm Canterbury’s (and England’s) precedence over the Welsh Church. This second part of the mission was causing Gerald a great deal of angst: it was his fervent wish that one day the Welsh Church, with its spiritual base in St David’s, would become independent of Canterbury and England and report directly to the Pope in Rome. It was the way things had always been, he believed, until the invading Normans had demoted St David’s to a mere bishopric, answering to the Archbishop of Canterbury. There was very little evidence for this (although in his books Gerald manages to manufacture plenty), but it was a cause to which the quarter-Welsh Gerald would devote much of his life. The truth is, Gerald longed to become the next Bishop of St David’s himself (one of his Norman uncles had held the post for many years) – and Gerald, who was ambitious, not to mention acutely aware of his own talents, allowed himself to dream of a moment when the Bishop of St David’s might one day morph into the Archbishop of All Wales.

None of this was ever going to happen, not so long as there was a Norman king on the English throne. If they allowed the Welsh Church to secede, then they might as well allow the whole country to go its own way. Most of Wales was independent at the time of the trip, but the Normans were palpably hungry for more of what they didn’t yet have. Twelve years earlier, in 1176, on the death of his uncle, Gerald had fought a bitter campaign to succeed him as Bishop of St David’s – and had only lost because he was, in the eyes of Henry II, suspiciously and dangerously Welsh. It was Henry, of course, who in 1170 had (perhaps accidentally) ordered the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, for showing too much independence. All of this was recent history to Gerald, but his ambitions were taking him to a dangerous place.

The ma

n who had beaten Gerald to the Bishopric of St David’s, a Norman called Peter de Leia, was also riding with Baldwin, presumably keeping his distance from the acerbic and voluble Gerald. It was here in New Radnor, at the end of a long day’s ride from Hereford, that the archbishop gave his first sermon on the taking of the Cross and as soon as it was over, with the final ‘Amen’ floating away into the surrounding hills, Gerald leaped to his feet and hurled himself at Baldwin’s feet, vowing that he would follow his king and Church on a death-or-glory crusade to the Holy Land, so help him God. He was the first person in Wales to take the Cross, or so he tells us, just as he makes a point of mentioning that the next person was the current Bishop of St David’s, Peter de Leia (too slow, Peter, too slow …).

What we know about Gerald comes almost entirely from his own writings. At the time of the trip he was about forty-two years old, a tall, vigorous man, breathtakingly handsome (as I say, Gerald is his own source), with strikingly shaggy eyebrows and a piercing eye. He had grown up in Manorbier in south Wales in the castle of his Norman father, probably learning Welsh from his mother. He spoke Norman French by default and wrote, he tells us, in ‘the most beautiful Latin’. (Alas, I’m no judge. After spending ten years not learning the language, all I can say for sure is that being able to misquote Latin epigrams does not make you Disraeli.) He compared the speech of the English to the hissing of geese, and saw no need to understand the witterings of a humiliated peasant race. He was brilliant and shrewd and always destined for the Church, and was sent away aged eight to study with the monks at Gloucester Cathedral, before heading to Paris as a teenager to learn philosophy with the best. He was hugely ambitious (the diocese of St David’s might as well have been carved on his heart), witty, questioning, energetic, scheming, combative, loved a good story (the wilder the better), but he became bitter in later years when his dreams of St David’s were thwarted. Baldwin, whom Gerald dismissed as an amiable but ineffectual holy man totally unsuited to the post of archbishop, would have been delighted to have him along for the ride, even though it wasn’t long before he found himself having to read out loud from Gerald’s books every night of the trip.

It is peaceful here, and still early, high above New Radnor on the Norman earthworks, in the place where Gerald pledged his allegiance to the Holy Cross. There’s no other trace of the castle: its stones were removed long ago to feed the walls of the church and the villagers’ homes. All that remains is a series of stepped, damp, grass-covered mounds and ditches, and a vast ancient ash tree, only just coming into leaf on this first day in June, a solitary hawthorn surrounded by the stumps of other fallen trees, dense clusters of nettles and, on the southern slope, above some advancing elder trees, a mazy rush of golden young buttercups, muted in the drifting fog. An army of moles has been busy enjoying itself in the absence of any human interference; and far below in the village I can just make out a child’s bright yellow trampoline in one of the back gardens. A sheep on a distant hill gives a petulant bleat from out of the mist.

A lot has happened in the 830 years since Gerald, Baldwin, Bishop Peter and their accompanying retinue of clerks, clerics, servants and soldiers gathered around this hill. And yet, really, not so much.

In 1188, Wales was ruled by a chaotic jumble of Welsh princes and Norman knights, the latter taking care to acknowledge the primacy of their king, Henry II. In the south, the most important Welsh leader was the Lord Rhys. He had come to New Radnor to greet Archbishop Baldwin, who had not only brought Gerald with him to keep things civil (Rhys was one of Gerald’s many Welsh cousins), but also Henry II’s most powerful adviser, Ranulph de Glanville, who was here, not so subtly, to make sure that the Lord Rhys wasn’t going to give any trouble. Once that was clear, he headed back to England. It was a time when ‘wealth and violence’, as Gerald put it, were the ultimate answer to anything, with violence usually the more certain route. In 1063, just before the Norman Conquest, Harold, the last Saxon king, ‘had marched up and down and round and about the whole of Wales with such energy that he “left not one that pisseth against a wall”’. According to Gerald it was only because of the destruction wrought by Harold and his English soldiers that the Norman kings had managed to subdue Wales. Now the south of the country, and the border with England, were studded with the castles of Norman lords who had grabbed what they could and held it against Welsh retaliations and sometimes each other. Gerald’s Norman grandfather was one of these lords who’d chosen to blend bloodshed with diplomacy and marry a local Welsh princess.

Baldwin and Gerald were travelling through a violent land, although I doubt they’d have been under any threat. They had their soldiers, after all – and anyway their arrival in a town or village would have been a major thrill to almost everyone. Here was the Archbishop of Canterbury, the first ever to visit Wales, and he had the God-given power to forgive sins, heal the sick, cast out the devil and excommunicate the wicked. People would have rushed to come and hear him speak; in Cardigan, Baldwin was almost crushed to death by a frantic surge of would-be crusaders. So although Gerald and Baldwin sometimes grumbled about the state of the roads (there were none to speak of, apart from the remnants of a Roman road along the south coast) and the godawful weather (this is Wales), and Baldwin fretted about the crusade – despite all that, I get the feeling they were both thoroughly enjoying themselves.

From New Radnor the recruiting party made its way west to Castle Crug Eryr, where they signed up the Welsh Prince of Maelienydd, ‘despite the fears and lamentations of his family’. There they turned south, probably past the little church of Glascwm (rebuilt since Gerald’s day, although it’s possible the same yew trees were there to welcome us both). Inside the church there’s a sign marking the ‘safe return’ of five local men from the 1939–45 war; and just next to this, propped against a wall, is a white wooden cross commemorating Oberleutnant G. Brixius of the German Air Force, who died when his plane crashed nearby in 1942. Gerald would have approved, I reckon. Despite his many criticisms of the English, Welsh, Flemish and others, he had a thoroughly medieval understanding of what it means to be human. A race may be punished or rewarded for its behaviour (the Welsh, for example, had been driven to the western edges of Britain because of their well-known and unfortunate predilection for incest and homosexuality), but we are all one family under God.

The route south took Gerald through Hay-on-Wye, once deep into Wales, now a town on the border. The travellers were met by a great crowd of would-be crusaders, running towards the castle, ‘leaving their cloaks in the hands of the wives and friends who had tried to hold them back’. The annual literary festival is in full swing and I sit for a while under the walls of this castle, with the bunting flapping above and a smell of venison burgers and cumin hanging in the air. Despite the use of the Welsh language on almost every poster, street sign and handout, Hay during its festival is thronged with English-speakers, most of them, it seems to me (as my eye drifts down a bewildering list of quinoa and kelp smoothies), from the suburbs and surrounds of England’s wealthier cities. Well, that’s fine, let’s hope (for here I am), and it is undeniably better that these mostly sensitive and eager-to-accommodate (but at times utterly oblivious) foot soldiers of English globalization should be wearing their Hunter boots rather than the chain-mail shirts and iron gauntlets of Baldwin’s day. But let’s not kid ourselves how we got here. As Ithell Colquhoun once wrote about her beloved Cornwall, a part of Britain less secure in its otherness: ‘The Cornish language did not die a natural death; it was executed like a criminal by the oppressing Saxon power.’

The dominant local Norman baron of the day was a man called William de Braose and he ruled over Hay, although his main base was at Brecon Castle, just a short walk from Gerald’s official home in Llanddew. He was an undeniably violent man, fond of stealing Church property and slaughtering the locals, but Gerald is strangely silent on all of this, instead claiming that de Braose was so pious that it became quite boring the number of times he invoked the Lord’s na

me in everyday conversation and correspondence. Maybe Gerald was trying to get his backing for his St David’s schemes. He also slobbers all over de Braose’s wife, Mildred (‘a prudent and chaste woman’), even though she is better remembered for her terrifying brutality – she ate babies, you know – and was starved to death, with her son, in King John’s dungeons once her husband was safely out of the way. Gerald also has surprisingly little to say about his local town of Brecon, so it’s interesting to go and stare at the bald statements of power – castle and cathedral – and wonder where that power has gone today. Not the cathedral, that’s for sure. It feels sleepily Trollopian, although its elegant east side was only made possible with an infusion of de Braose’s blood-drenched plunder.

Baldwin had turned south at Brecon, still keeping close to the border, heading for Abergavenny, Cardiff and the south coast. Gerald keeps us amused, as he must have done Baldwin, with a succession of miraculous tales. There’s one about a woman in the north of England who sat down without thinking on the wooden tomb of Saint Osana and found herself stuck there, unable to move, until the people came and stripped her naked and whipped her for the crime. It was only once she had prayed and wept for forgiveness that her ‘backside’ was unglued. And, as they trotted along, Gerald told Baldwin about Brecknock Mere (we know it as Llangorse Lake), to the east of Brecon, which sometimes turns bright green, or flows with red blood, and at other times is covered with gardens, ornamental buildings and orchards, and harbours the most delicious eels and pike. There was a legend that the rightful ruler of the land could conjure the birds of the lake to sing to him; and once, when the Welsh lord, and Gerald’s great uncle, Gruffydd ap Rhys ap Tewdwr was riding at its side with two Norman knights, in the time of Henry I, all the birds did just that, thronging Gruffydd with song and acclamation, while ignoring his Norman friends, and Gerald must have taken pleasure in telling Baldwin just what Henry I had said when he heard this story:

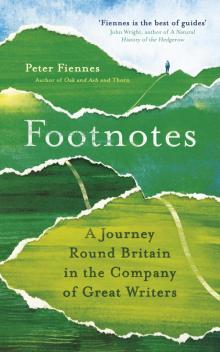

Footnotes

Footnotes