- Home

- Peter Fiennes

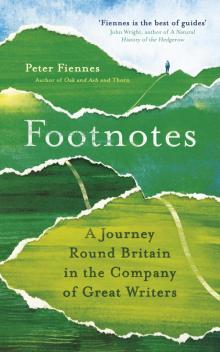

Footnotes

Footnotes Read online

Praise for

Oak and Ash and Thorn

A Guardian Best Nature Book of the Year

‘Extraordinary … Written with a mixture of lyricism and quiet fury … Fiennes’s book winningly combines autobiography, literary history and nature writing. It feels set to become a classic of the genre.’

Alex Preston, Observer

‘Steeped in poetry, science, folklore, history and magic, Fiennes is an eloquent, elegiac chronicler of copses, coppicing and the wildwood.’

Sunday Express

‘A passionate ramble through Britain’s complicated relationship with its woodland.’

Daily Mail

‘Fascinating … This passionate book should inspire readers to plant more trees, support woodland campaigns and participate in active conservation.’

BBC Countryfile Magazine

‘Lyrical, angry … I loved it.’

Tom Holland

‘Rich, personal, evocative, rousing.’

Robert Penn, author of The Man Who Made Things Out of Trees

‘A wonderful wander into the woods that explores our deep-rooted connections – cultural, historical and personal – with the trees.’

Rob Cowen, author of Common Ground

‘Peter Fiennes really can see the wood for the trees – he blends mythology, natural history and a sense of righteous anger to produce a paean of praise to our ancient woodlands and modern forests, and the life support system they provide.’

Stephen Moss, author of Wild Kingdom

‘A tender hymn to the trees, a manifesto for a woodland society, a contemporary gazette of ideas and attitudes radiating into the future like annual rings from the original pith … In this lyrical, informative, unashamedly arboreal propaganda, one man’s walk in the woods can inspire a generation.’

Paul Evans, author of Field Notes from the Edge

‘Fiennes is the best of guides, gently, eloquently and with a fierce humour telling a sad story – relating chapters of fascinating detail to brighten his tale and quoting the poets as he goes.’

John Wright, author of A Natural History of the Hedgerow

In memory of my parents: my father, Michael Fiennes, 1912–1989, whose modest presence appears in these pages at least twice; and my mother, Jacqueline Fiennes (née Guilford), 1922–2001, who brought life and laughter to everything.

And for Anna, of course, as ever.

‘He’s gone: but you can see

his tracks still, in the snow of the world.’

Norman MacCaig, ‘Praise of a Man’

Contents

Preface

1: ‘I Am Your Storyteller’

Enid Blyton, Swanage and the Isle of Purbeck, 1940–1960s

2: ‘Walk, and Be Merry’

Wilkie Collins, Plymouth to Lamorna Cove, July and August 1850

3: Pilchards to Postcards

Wilkie Collins & Ithell Colquhoun, Lamorna Cove to Launceston, 1850 and 1950

4: Backtracking

Celia Fiennes, Launceston to Hereford, 1698

5: ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’

Gerald of Wales, South and Central Wales, March and April 1188

6: ‘Lorf? – Why, I Thought I Should ’a Died’

Edith Somerville & Violet ‘Martin’ Ross, Welshpool to Chester, June 1893

7: ‘The Secret Dream’

J. B. Priestley & Beryl Bainbridge, Birmingham to Liverpool, 1933 and 1983

8: ‘The Doncaster Unhappiness’

Charles Dickens & Wilkie Collins, Cumberland to Doncaster, September 1857

9: A Wilderness

Samuel Johnson & James Boswell, Edinburgh to Skye and back, August to November 1773

10: Fog on the Tyne

J. B. Priestley & Beryl Bainbridge, Tyneside to Lincoln and London, 1933 and 1983

11: Last Supper

Everyone. Somewhere. Sometime.

12: Larger Than Life

Charles Dickens, Gad’s Hill to Westminster Abbey, 14 June 1870

The Company of Great Writers

Acknowledgements

Permissions

Select Bibliography

Footnotes*

* ‘… post this, post that. Everything is post these days, as if we’re all just a footnote to something earlier that was real enough to have a name of its own.’

Margaret Atwood, Cat’s Eye

Preface

‘But once in my life … I did have a feeling that the world was a phantom. That was when I was in England.’

Nirad C. Chaudhuri, A Passage to England

The premise of this book is simple, or that is what it seemed when I started. I was going to travel around Britain in the footsteps of a succession of (mostly) famous writers, without leaving any gaps, and without straying from their recorded paths, passing from one to the next like a baton in a relay, or a snowball swelling as it rolls, picking up people and debris along the way. I was keen to take in as much of the country as I could, but I also decided, for no good reason, that the journey should unspool in one continuous loop.

My first idea was to organize the route chronologically. The earliest journey made here is by Gerald of Wales (1188) and the most recent is by Beryl Bainbridge, who smoked her way around England almost eight hundred years later. But then I thought it would be more interesting to move from childhood (Enid Blyton in the Isle of Purbeck) to death (Charles Dickens, whose corpse was shunted by train from his home in Gad’s Hill, Kent, to Westminster Abbey). The ghost of that second idea remains, faint traces of the Seven Ages of Man (there’s even a mid-life crisis), although we all know that the best journeys never go entirely to plan.

I was pleased I started with Enid Blyton. Her influence runs deep in all of us, I came to believe – or at least her idea of what Britain should be has proved surprisingly tenacious. I nosed around her life and Footnotes became an attempt to understand her, and the other writers, by looking at the places they had travelled through and written about. Enid is the only one who doesn’t actually go anywhere. That seems appropriate, but I was also happy to discover that she is a much more interesting person than we have been led to believe.

Footnotes also started as a rather grandiose attempt to bring modern Britain into focus by peering through the lens of past writers. I steeped myself in what they had seen and witnessed, tried to adapt to the different ways they thought, absorbed what mattered to them and the tenor of their times … and then stepped into the present. Sometimes it can take a shock, like getting off a train in a foreign land, to open our eyes and ears. Of course it was hopeless. ‘The diversity’, Orwell wrote, ‘the chaos!’ But one of the connecting threads of this book is an examination of what conservationists call ‘shifting baseline syndrome’, the disorientating idea that as every generation passes, our understanding of what is ‘normal’ moves, without us even realizing it. We can no longer remember, or we have no direct experience of what it was like, to live in a different world. In short, how do we know whether life is getting better, or worse? And not just for humanity. Especially not that. Because surely by now we have all got the message that our lives are not separate from everything that connects and supports us. We urgently need to lift our eyes and take the long view.

Anyway, I should quickly add that I also managed to have a lot of fun, following this opinionated band of writers around Britain. We live in a beautiful land. I indulged a lifetime’s obsession with old guidebooks. There is so much to enjoy, from the wilds of Skye and Snowdon to the big night out in Birmingham. And the people. They are so friendly and open. Until, just occasionally, they are not. Of course it is ludicrous to generalize, but even so I did find myself succumbing to a sneaking desire to say something about identity. Who are we? What do we want? They seemed like good quest

ions to ask, in the company of some of our greatest writers, given these restless times.

Peter Fiennes, London, 2019

One

‘I Am Your Storyteller’

‘Oh voice of Spring of Youth

Heart’s mad delight,

Sing on, sing on, and when the sun is gone

I’ll warm me with your echoes

Through the night.’

Enid Blyton, Sunday Times, 1951

Enid Blyton,

Swanage and the Isle of Purbeck, 1940–1960s

It is April in the Dorset seaside resort of Swanage and the town is struggling to emerge from a long and grisly winter. Not ice-bound, exactly, but the last few months have been dank and chill and unremittingly dreary. Only last week, the ‘Beast from the East’ had lashed the peninsula’s narrow lanes and calcareous hills with a clogging, heavy snow; now it has returned (a ‘mini-beast’ the papers are calling it), but this time with a supercharged wind, gusting up the Channel, flailing a couple of panicking teenagers on the esplanade and shepherding the town’s elderly smokers into the uneasy sanctuary of the bus shelter. Everything, everywhere, is being clawed and rummaged by a foul sleet and the streets are slick with last season’s grime. It is, I am certain, the kind of day that Enid Blyton would have described as ‘lovely’.

Enid Blyton had no time for bad weather. There really is no such thing if you are wearing the right clothing. And perhaps that is why she always spent her holidays in Swanage and almost never visited sunnier lands. There may have been other reasons, but anyway she was ambivalent about America, disliked Walt Disney and – while we are at it – was perpetually disappointed in the BBC. Nor did she much care for children who had no interests other than the cinema; nor spoiled, selfish and conceited children; nor mothers who left their homes and their husbands to pursue careers (although this is undeniably odd given her own hard-fought success). As soon as she could, she avoided her brothers and cut her mother dead. She disapproved of divorce, and first husbands (the heavy-drinking type), and the sour opinions of grown-ups, and said she loathed lies and deceit. She was desperately unhappy if she couldn’t write, but hated sitting still. And when she was writing, she feared (but used) her subconscious and avoided convoluted plots. She found other people’s illnesses alarming or tiresome, along with people with ‘inferiority complexes’, or anyone who gives up; and she preferred children who are ‘ordinary’ or ‘normal’ (although where did that leave her own two daughters?); and she disapproved of cruel, sad tales (Grimm in particular), and girls who think of nothing but boys (‘disgusting’), and things that are frightening, and cruelty to animals and birds (especially that: ‘I think both those boys should have been well and truly whipped, don’t you?’); and interruptions to her work; and silence.

So, it is complicated. And I am sure it would be just as easy for any of us to draw up a list of the things that rile and enrage us – but it is good to remember that there was as much (and more) that Enid Blyton loved. Practical jokes, for example, and laughter. Birdsong. Cherry blossom. The sight and feel of cut flowers. The sea. Summer holidays in the Isle of Purbeck, when she would put aside her typewriter and swim around the pier and play tennis, and finish the prize crossword, and read Agatha Christie novels, and take long walks across the moors, and play with her children, Gillian and Imogen, and transfuse her love of nature straight into their eager young hearts. A round of golf (or sometimes three) in the afternoon. Country lanes. A game of bridge (especially winning). The sunshine of the woods and commons. Her dogs, gardens and husbands. Writing. Writing. Writing. But above all she bathed in the love of the millions of children who devoured her books, and clamoured for her attention, and came to her readings, and joined her clubs, and pursued her with gifts and letters, and visited her at Green Hedges, the large, mock-Tudor home she named and nurtured in Beaconsfield (although, we still have to ask: where did that leave her own two daughters?).

Enid Blyton adored Swanage. Once she’d discovered the place (in the spring of 1931, on a day trip from Bournemouth where she was holidaying with Hugh Pollock, her first husband, and pregnant with her first child, Gillian), she came again and again, often three times a year, sometimes staying for weeks at a time. On that first trip, as she told the ‘Dear Boys & Girls’ in a letter to Teachers’ World, she came soaring over the hills on the road from Wareham, driving her ‘little car’, and saw ‘the ruin of an old, old castle’ on ‘a rounded hill’. It is hard to shake the idea (it’s the way she writes) that here is Noddy, rattling into Toyland with grumpy old Big Ears in the passenger seat, rather than Enid crying with delight at her first glimpse of Corfe Castle (and Hugh, hands tight on the wheel, his mind already drifting towards the first strong drink of the day in the lounge bar of the Castle Inn).

The castle hasn’t changed much since. Excitingly, the jackdaws that Enid wrote about are still here, dozens of them, puffing up their grey-black feathers and asserting noisy ownership over the ruined battlements. On the day I visit, and sit where Enid once sat, on the soft grass that now covers the old moat, I find their bright, blank gaze disturbing. They stand too close, watching all the time, and seem to be choosing which part of my flesh they’d like to snag with their sharp beaks. But Enid loved them. ‘“Chack!” they cried, “Chack, chack!”’ as she wrote in her letter to the young readers of Teachers’ World; and then, in the very first of the Famous Five books, Five on a Treasure Island, here they are again, swarming all over the ruined castle on Kirrin Island, ‘Chack, chack, chack!’ – with Timmy the dog leaping into the air and snapping at their cowardly hides.

Everyone is convinced that Corfe Castle was the model for Kirrin Castle, but Enid would never say, and when I ask the taxi driver if it is true (he’s a local man, brought up in Corfe, speeding me through the village on the road from Wareham Station to Swanage), his answer is a succinct and scornful ‘No’. It is possible he just doesn’t want to talk about Enid Blyton. If you only have the output of the BBC to go on, or the memoirs of her second daughter, Imogen, then you are going to be under the impression that Enid was a dysfunctional narcissist, a cold-hearted snob, a racist and the worst of mothers who preferred the company of children she’d never met to the grating shrieks and demands of her own. Perhaps the people of Corfe have had enough of the association. Until recently there was a Blyton-themed shop in the village, called Ginger Pop, but the owner closed it down because the guardians of Enid Blyton’s copyright were traducing her memory with a load of overpriced spin-offs and politically correct rewrites. At least, that’s how she saw it. She was also irritated by tight-fisted browsers who told her what a lovely shop she was running, but then wandered out without buying anything. There was also, apparently, a spot of bother about some golliwogs in the window.

Anyway, my taxi driver is much more interested in talking about the second homes that are sucking the life out of the village. Enid Blyton never owned a house here, although in 1956 she did buy a farmhouse in north Dorset. She didn’t live there – it was rented and used as a working farm – but she did set her eighteenth Famous Five book, Five on Finniston Farm, in its ancient and mysterious passageways. In 1940 Enid had decided to take a room with her two young girls at the Old Ship Inn in Swanage. The place was hit by a Luftwaffe bomb later in the war, after which she tried the Marine Villas on the front and then, as her fame and fortune blossomed, she moved on to the Grosvenor Hotel (since demolished, mercifully; it looked as ugly as a burst spleen). When she tired of the Grosvenor’s pretensions, she tried the Grand on the east side of town, which is where I’m heading.

The taxi driver has moved on to the topic of crime. He says there is none (or nothing worth mentioning), and that the people of Purbeck just step out of their homes leaving their front doors unlocked without a backward glance. This is also just about the first thing the late-night barman tells me when I arrive at the Grand (‘I moved here from Kilburn and it’s nothing like that; it’s more like you’re living in the 1950s or ’60s. No one eve

r locks their doors’). And again with the two other taxi drivers I meet on the Isle of Purbeck (‘Leicester’; ‘1960s’; ‘Huddersfield’; ‘1950s’; ‘never lock my front door, ever’). I can only hope that there are no burglars reading this (living in the here and now, finding it hard to make ends meet among the well-locked doors of London or Liverpool). They’d fill their boots.

Still, this is clearly something that draws people to the Isle of Purbeck. The hope that they can sidestep everything that has gone wrong elsewhere: splintered communities, broken homes, soaring crime rates, metrification. It’s a backwater wrapped in a time warp. And although the Isle of Purbeck is not a real island (it’s a peninsula, in the shape of an upside-down goat’s head, bounded by the River Frome to the north and a small stream near East Lulworth to the west), I suspect this desire to seal herself off is what brought Enid here too. Even in 1942, when Vera Lynn’s latest hit, ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, was playing from every gramophone in the land, Swanage must have felt like a place out of time and cut off from the rest of Britain.

There are mixed messages about Swanage in the guidebooks of Enid’s day. In 1935 Paul Nash denounced the place in the Shell Guide to Dorset as ‘perhaps the most beautiful natural site on the South Coast, ruined by two generations of “development” prosecuted without discrimination or scruple’. The Penguin Guide to Wilts and Dorset (1949) is more forgiving, and I prefer to think Enid had this one on her hotel bedside table. ‘Swanage’, the writer purrs, ‘is an outstanding example of the little fishing village grown up into something better.’

Today, the brutal wind is making it hard to get a fix on Swanage. A mucky brown scurf has gathered in foamy clumps where the sea meets the shore. It is especially thick at the groynes, where occasionally it is whipped up and flung onto the esplanade, scattering into tiny flecks that fly through the air before fizzling out on the windscreens of neatly parked cars. Inflatable beach toys are bucking against each other in the shop fronts, shaking off sprays of sleet and squeaking in plastic distress. Damp bunting is pressed against the awnings. The shops and streets are almost deserted. It’s cold outside, but inside the Ship, where Enid (aged forty-two) stayed with Gillian (eight) and Imogen (five) in 1940, they are showing a Premier League football match on the wall-filling TV and there’s the close, happy atmosphere that all good pubs have when the afternoon is young, the weather is wild, a fire is burning, and everyone has decided that they might as well stay for another. A man leaning heavily on the bar tells me that the local Purbeck beer is good, but he draws a blank when I ask him about Enid Blyton. He moved here recently from somewhere in the North (Preston, was it?), and (gesturing vaguely) lives just up the road. I ask if he has locked his front door and he gives me a sharp look.

Footnotes

Footnotes