- Home

- Peter Fiennes

Footnotes Page 2

Footnotes Read online

Page 2

In mid-1940 Enid had been married to Captain Hugh Alexander Pollock for fifteen years, although Hugh was not on holiday with his family this time. He was probably at home at Green Hedges, helping organize the local Home Guard, which he’d joined a few months earlier. Hugh was a veteran of the First World War, too old to fight in this latest conflagration (he was fifty-one), but desperate to do something. He’d first enlisted in 1912 – he was an army regular by the time the First World War started – and for four years he’d seen almost continuous service in Gallipoli, Palestine and France. After the war ended, he’d stayed on as a temporary captain in the Indian Army, before becoming an editor at the London publishing company George Newnes. It was here, almost as soon as his feet were under the desk, that he had written to Enid Blyton, an inordinately ambitious, but so far only moderately successful, children’s author, and suggested that they collaborate on a book about zoos. He met her for the first time, briefly, in his offices on 1 February 1924, an event marked by Enid in her diary:

Met Phil [a female friend] at 2.45 & we went & had coffee together till 3.30. Then I went to see Pollock. He wanted to know if I’d do a child’s book of the Zoo! He asked me to meet him at Victoria tomorrow to go to the zoo. I said I would. Home at 5.

Now, I don’t know how much of what follows was commonplace in the world of publishing in the 1920s, but Hugh clearly had more on his mind than books and zoos. His transparently cunning suggestion was that he and Enid should meet at Victoria station (she would travel up from Surbiton, taking time off from her work as a nursery governess), before proceeding to Regent’s Park and London Zoo, where they could discuss the possible book. In the event, things moved bewilderingly fast, as Enid noted in her diary entry for 2 February, the very next day:

Met Hugh at two. Went to the Zoo and looked around. Taxied to Piccadilly Restaurant and had tea and talked till six! He was very nice. We’re going to try and be real friends and not fall in love! – not yet at any rate. We are going to meet again tomorrow.

And so they did. The next day they were discussing ‘the zoo book’ over a long walk in the park followed by tea in the Piccadilly restaurant. Enid was dazzled by this trim, authoritative, older, military man (he was thirty-five to her twenty-six). And when Hugh (after just two days) tried to suggest to the ferociously focused Enid that their friendship should be ‘platonic for 3 months’ and (in a letter written on 5 February) that he was ‘fond’ of her in ‘a big brotherly sort of way’, Enid raged in her diary: ‘I’ll small sister him.’ The next day (just four days after they had met for the first time), Enid wrote:

Wrote a long letter to Hugh till 9 telling him exactly what I think. Guess he won’t like it much, but he’s going to fall in love if he hasn’t already. I want him for mine.

And that was that. If Enid ever wanted something, she tended to get it. Sure, there were some hurdles along the way, but the end was never in doubt. For one thing, Hugh had to let his first, estranged wife know that he wanted a divorce. He’d married Marion Atkinson in 1913 and they’d had two boys (the elder, William, dying in 1916). Marion had left Hugh for another man when he was away fighting – and I’m sure this rejection explains another part of the appeal of Enid for Hugh. In most ways she really was very young for her years, and Hugh craved unwavering commitment.

Progress, as mapped out in Enid’s diary, was breathless. On 21 February she had ‘a glorious love letter from Hugh this morning. Such a lovely, lovely one. He is a lovely lover.’

On 23 February ‘We had taxied to Victoria and Hugh took me in his strong arms & kissed my hair ever so for the first time. We had dinner at Victoria & I caught the 10.30 train. It was a lovely, lovely day. I do love dear, lovely Hugh.’

On 29 February they went to their first dance together (‘I loved it & loved it’), and through March they dined at Rules in Covent Garden and strolled in Embankment Gardens and the Tivoli. By the end of the month they were shopping for signet rings together. In mid-April they were on holiday in Seaford (‘We went for a walk to Hope Gap, & sat on the downs, & Hugh was a darling lover’); she missed him horribly when he went back to London. In early June Hugh presented Enid with a ring (‘it’s a LOVELY one’). July found them flat-hunting in Chelsea. And on 28 August 1924 they were married at Bromley Register Office. It was a small affair – with no room for her mother.

If Hugh was looking for uninhibited innocence, someone to soothe his wartime nerves with love and fill his days with chatter and japes, then Enid (who’d hardly been to a dance, or dated a man, but who was burning with pent-up desire for a husband, and her own children, and kittens, and a fox terrier, and a cottage with roses and honeysuckle clambering at the door and her very own garden, heaving with hollyhocks, pixies and frogs), then Enid was manna from heaven. And perhaps what Enid didn’t notice, or understand, was quite how deeply Hugh had been scarred by the war. Even in their first weeks they would ‘row ferociously’. They argued over who would be ‘master’ in their marriage and after a miserable day Enid was glad to tell Hugh that it would be him. Enid gave her ring back at least once. She discovered that Hugh could draw from a bottomless well of possessive jealousy – he even managed to be suspicious of an unknown man who was coming to stay in their boarding home when he and Enid were taking a short (chaperoned) holiday. On 7 May she had written in her diary: ‘But oh I do so wish he would get over his jealousy. It makes me afraid of marrying him.’ And perhaps, also, Enid didn’t grasp the significance of Hugh’s frequent ’flus and food poisonings and occasional absences and dark moods. He had surely been drinking hard since the war, and despite Enid’s hopes that she had found someone ‘masterful’, she (with her unwavering certainty and bright clear path to the future) was in truth a lifeline flung to a floundering man.

And they loved one another – wholeheartedly and thrillingly. It’s too easy to poke around someone’s diary (especially, let’s face it, Enid Blyton’s) and find things to snigger at. Her language is limited (just how ‘lovely’ can everything be?) and at times jarringly old-fashioned. She buys a ‘ripping new attaché case’. They go to see Jackie Coogan in Long Live the King and ‘it was topping’. She misses Hugh when he’s not there and ‘it’s BEASTLY’. His ‘eyes were as blue as the water’ she confides, or sometimes ‘the sky’, and on 22 March, on Hugh’s first visit to her home, ‘We stayed in the drawing room by ourselves and Hugh loved me tremendously.’ But not like that! Because before you start imagining a scene that never unfolded (or at least not yet), it turns out that on this occasion Enid was simply sitting at Hugh’s knee while he read Kipling at her.

It is hard to believe that there really was a time when millions of people talked as though they were stopping off for tea and a restrained and unconsummated affair at a station café in Carnforth. Clipped and constipated. Ripping and topping. But there they all were (it wasn’t just something they put on for the films and the newsreels) – and (to state the bleeding obvious) their emotions and actions were just the same as ours. To take one tiny example, here is an entry in Enid’s daughter Gillian’s diary from July 1946: ‘Today I got 7 for French. We swam in gym. It was wizard.’ And indeed I grew up in a household where my mother (born 1922) was always asking me to ‘go and make love to’ my aunt or the elderly next-door neighbour, and all she expected (I presume) was for me to ask them nicely to lend us some sugar or help with the hoovering. Perhaps what needs saying is that the language Enid Blyton uses in her books may have dated, but it was undeniably authentic.

Anyway, enough of that. The weather hasn’t improved when I finally drag myself away from the public bar of the Ship Inn, but I am eager to get on the trail of Enid Blyton. She knew these Swanage streets well – she used to sign books at Hill & Churchill’s bookshop (now closed) and take long daily swims from the beach (a horrible thought on this bitter day). And it was here, in 1940 (with the beach closed and littered with tank traps and the town alert to the possibility of spies and fifth columnists), that she came up with the idea of the Famous F

ive books, a series of rollicking adventures starring four gloriously unsupervised children and a monomaniacally heroic rescue dog.

Swanage would have been smaller in Enid’s day: more compact and Victorian. But it’s still an easy, fun-loving place (I can see that much through the driving sleet), and its essence is surely unchanged: a fishing village turned pleasure beach, with big wide skies looping over a great scoop of a bay, flanked by low, treeless hills. There’s a jaunty pier, in front of which are the Georgian Marine Villas, where Enid and the children stayed in the summer of 1941. It seems strange to think of Enid ploughing ahead with her summer holidays as the war raged, the children under strict orders to avoid the beach and the freshly poured concrete pillboxes, but instead heading inland to the moors, or east along the coast towards Old Harry Rocks.

That said, Enid had a talent for avoiding inconvenient or distressing developments and even a world war couldn’t disrupt her routine for long, or staunch the flow of words. In 1941 she published twelve books, despite paper shortages; in 1942 there were twenty-six, including Five on a Treasure Island. This ability (or desire) to ignore or blank what she didn’t want to see is not that unusual, of course, and the war years were a time of huge creative ferment for Enid, although it is also incredible to think that she only really achieved her final, world-conquering momentum in the 1950s. Barbara Stoney, in her biography of Enid Blyton, lists an eye-bleeding seventy (seventy!) books published in 1955, including – but most certainly not limited to – countless Bible and New Testament stories, Mr Tumpy in the Land of Boys and Girls, what seems like a dozen Noddy books, another Famous Five outing (the fourteenth), Clicky the Clockwork Clown, a Secret Seven book (the seventh), more adventures from Bobs, her long-dead fox terrier, Robin Hood, Neddy the Little Donkey, Enid Blyton’s Foxglove Story Book, Bimbo and Blackie Go Camping, something to do with golliwogs, Mr Pink-Whistle’s Party (good grief) – and on and on and on.

As I battle my way through the wind and the rain along the fringes of Swanage’s empty esplanade, I come across the Mowlem Swanage Rep Theatre, a squat, square, post-Enid building, heavy with glass and concrete, today showing Peter Rabbit. The very young and the elderly are well catered for in Swanage – you can see it in the many benches and greens and places selling sticky treats – and so indeed are dairy lovers. Parked out front of the theatre is a dark ‘Swanage Dairy’ van, on its side a nicely etched pledge, written large, to fulfil ‘all your dairy supplies’. I remember when my eldest daughter was young how much she loved her Noddy videos, in particular one called, I think, Noddy Helps Out (doesn’t he just), in which Toyland’s milkman is feeling droopily depressed about something. I have no idea what his problem was – I’m certainly not going to watch the damn thing again – but the tape played on an eternal loop, grimly soundtracked by the milkman’s plaintive cries: ‘Milk-O! Milk-O!’ and little Noddy’s insufferable laughter. ‘Milk-O! Milk-O-o-o!’ I have been haunted by his misery ever since. If you think about it, every single one of Enid Blyton’s stories is concerned with resolving someone’s unhappiness – the bullied are rescued, wrongdoers are punished and redeemed, the righteous are rewarded – although she was always adamant that the story was what mattered. The message (‘all the Christian teaching I had … has coloured every book I have written for you’) had to be smuggled in, ‘because I am a storyteller, not a preacher’.

Enid Blyton also said that the ideas for her stories, and the people and places she put in them, did not come from real life but from her prodigious imagination (no giggling at the back, not until you’ve become the world’s bestselling children’s author). She said that once she had enough to get started (perhaps the setting, the main characters and a hazy outline of the beginnings of the first scene) she only had to sit at her typewriter, empty her mind and everything (the people, the fairies, the teddy bears, dogs and dolls, the plot and the dialogue) would all just unspool onto the page. As she put it in a series of letters to the psychologist Peter McKellar, she lowered herself into a sort of trance – think of Homer and his Muse – and the words flowed. So if, say, she had decided to write about a girl’s boarding school, and she wanted the main character to be exceptionally naughty, she would close her eyes and a girl called Elizabeth and her friends and the scenes would appear. All she had to do was write them down. Conversations, jokes, names of characters … she said she didn’t even know where most of this stuff came from. It just billowed out of her.

In her early years she tended to write in the morning, or in the cracks in the day, but later, when she was a full-time author, she would carry on till sundown, working to a rigid routine, breaking at set times for lunch, letter-writing, the crossword, a spot of gardening, tea with the children and supper with her husband. If she wrote 6,000 words in a day that was generally enough to merit a mention in her diary. Over 10,000 were cause for celebration. A Famous Five book could be written in a couple of weeks. She wrote in her autobiography, The Story of My Life: ‘If you could lock me up into a room for two, three or four days, with just my typewriter and paper, some food and a bed to sleep in when I was tired, I could come out from that room with a book finished and complete, a book of, say, sixty thousand words.’

In all she wrote a staggering 750 books, but no one (not even Enid) could be quite sure about the exact number. She had them all lined up in her library at Green Hedges, but there was always a nagging feeling that there was something missing. And it wasn’t just the books. There was the poetry, the plays and pantomimes, the magazine articles (she edited and wrote most of Enid Blyton’s Magazine and Sunny Stories and poured out articles for Teachers’ World), the hundreds of thousands of letters to her young fans, the household she ran, the tennis and golf and gardens, and the adult play (never produced nor seen again after its rejection – it was, said her daughter Imogen, with damning relish, ‘shallow and trivial’ and ‘never reached the stage and would not have run for a week if it had’). There were the illustrations to organize and approve (she had an immaculate eye for what would work: just look at Eileen Soper’s exquisitely evocative Famous Five drawings; or the pin-perfect artwork by the Dutch artist Harmsen van der Beek for Noddy, who seems to have worked himself to death trying to keep up with Enid’s industrial output). And there were the printers to oversee, proofs to approve, publishing contracts to negotiate (she enjoyed that, and spread herself across several different companies), the interviews, the talks to children (and oh how she loved those talks). And her clubs! And the charities, her own and others; she was quietly generous with her time and her burgeoning fortune.

In short, Enid’s days were laden with work. She went to bed early, armed with one small medicinal sherry, got up early and got busy. She was heartbroken when, in the 1950s, people started to suggest that one person couldn’t possibly be solely responsible for this extraordinary deluge of print. She worked so hard, driven by ambition, of course, but also an absolute dedication to her reading public and a desire to get her message across, a message that as the years went by was deliberately posed as a riposte to all that money-mad stuff coming out of America and Disney. And then to hear the rumours that it wasn’t even her creating these lovingly crafted stories, but some kind of Blyton factory, staffed with bored typists, tapping away all day, slipping in the word ‘lovely’ every now and then, after all, how hard could this tosh be, right? It was agonizing. She was so upset that in 1955 she even sued some hapless young South African librarian, who had dared to suggest that ‘Enid Blyton’ was a fraud. Enid won the case, the librarian was forced to apologize, but it didn’t settle the rumours. And also: what kind of paranoid ingrate takes a librarian to court? What, people wondered, not for the first time, does Enid Blyton have to hide? For an author whose public persona was so intimately entwined with her works, this rosy-cheeked, country-dwelling, dog-loving, flower-gathering, pie-baking, laughing, hugging, storytelling mother of two adoring children – any whiff of some alternative reality was potentially devastating.

We can’t say th

at Enid Blyton invented the author-as-brand (that was probably Charles Dickens). In fact she wasn’t even the first children’s author to package up her life and her books into one appetizing and marketable story (I guess that would be Beatrix Potter), but it is hard to think of any other author, before or since, who worked so relentlessly on cultivating her own success and burnishing her public image. Once she had decided, as a young child, to become an author (and a children’s author at that), she was extraordinarily consistent in how she appeared to the world. She ploughed through every obstacle. She happily admitted to having received dozens (hundreds?) of rejection slips. We praise the resilience of others (think of J. K. Rowling writing in that Edinburgh café, shivering as she fumbled open yet another envelope of bad news), but with Enid Blyton her blinkered refusal to give in and go away is seen by some as rather sinister. Publishers who tried to reject her early stories and poems about flower fairies and thistledown were simply treated to more of the same. In the end most of them succumbed – particularly when they got a whiff of the sales.

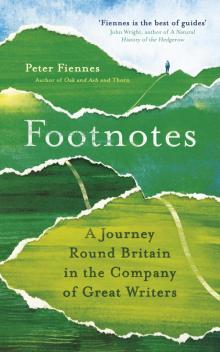

Footnotes

Footnotes